By Stan Maes & Véronique De Gucht, Leiden University, Netherlands

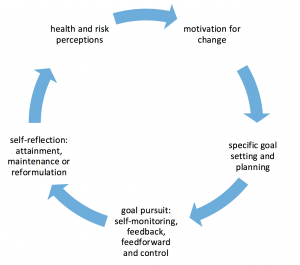

Over the last decades, the role of individuals within the healthcare system has evolved from ‘compliance with medical regimens’, implying obedience; to ‘self-management’, denoting responsibility for the control of one’s own health or disease. This has recently progressed further to the idea of ‘self-regulation’, a systematic process that involves setting personal health-related goals and steering behavior to achieve these goals. To illustrate the continuous self-regulation process, we have chosen the ancient image of an ‘ouroboros’ (i.e., a snake eating its own tail) to accompany this blog post.

Self-regulation occurs in phases: (1) goal awareness and goal setting; (2) active goal pursuit and (3) goal attainment, maintenance or disengagement. In the following paragraphs, we illustrate these phases using the example case of an individual, John, who has suffered a heart attack.

Phase 1

In the first phase, individuals should become aware of and set realistic and personally-relevant health-related (change) goals. For example, John might be asked, ‘What would recovery be for you?,’ to which he might reply that taking nature walks with his grandchild is important to him. As a first step, John might therefore set a goal such as ‘starting short walks in my neighborhood.’ It is important here that such goals are self-set and are realistic considering current functioning, as these give a sense of ownership and are more easily attained than goals imposed by others. Techniques of motivational interviewing can help to support personal goal setting among unmotivated individuals.

Phase 2

The second phase is characterized by goal pursuit. In this phase, individuals must bridge the common gap between cognitions (e.g., intentions) and action. For this purpose, a specific ‘action plan’ is needed, based on reflection, which specifies precisely when, where and how to act. In our example, this might be: ‘From next week onwards, I will walk with my wife to a nearby grocery shop to buy food on Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 3pm’. Action plans like this, which specify sufficient detail, have been shown to enhance achievement of goals related to physical exercise, healthy eating and other health behaviors.

In addition, three regulatory mechanisms play important roles during goal pursuit. The first of these is feedback, which involves monitoring and evaluating progress. In our example, John could be asked to register his activity to see whether he met his goal. The results could then be reviewed with John to either identify successes, or to identify problems to overcome in the future. The second mechanism involves anticipatory or feedforward processes, which include outcome expectancies (i.e., what a person thinks will happen if they take action) and self-efficacy beliefs (i.e., whether a person feels that they can successfully take action). Outcome expectancies and self-efficacy are both enhanced by observation of successful others, goal progress and encouragement. Clinicians should therefore provide contact with other people who successfully achieved comparable goals, to increase the chances of goal achievement and provide individuals with opportunities to receive support for their goals. The final mechanism involves activating control processes to ensure continued efforts despite competing goals or obstacles. A distraction from the self-set goal, e.g., by a life event, may have a detrimental effect on goal pursuit. Lack of progress toward goals (i.e., failure) is also frequently related to negative mood. If this occurs, one might want to offer John support for dealing with these emotions and help in coping with failure, by seeing these as opportunities for learning.

Phase 3

The third phase regards goal attainment, maintenance and disengagement. Goal attainment is not the end, but rather a new beginning. Individuals can be encouraged to set new goals to maintain progress over time. If however, a self-set health goal proves to be unattainable, it is often wiser to disengage from this goal and choose a more manageable goal. In our example, John could therefore continue pursuing his actual physical activity goal, or rather set a new goal such as going for a short daily walk with his dog. Fostering self-efficacy and social support are again important predictors of maintenance.

Much research has supported the efficacy of self-regulation based interventions for health behavior change in healthy populations and among patients with chronic illnesses, e.g., for weight loss in type 2 diabetes, for physical activity among people with arthritis, for lifestyle change in cardiac rehabilitation, and for balancing activity and rest in chronic fatigue syndrome.

Practical recommendations

1) Support the individual in formulating a personal change goal related to a relevant health issue (e.g., ‘What would represent recovery for you?’). These goals should be specific, important to the individual, not too easy or too difficult and attainable in a restricted time frame.

2) Assist the individual in building an action plan by asking when, where, how and how long the patient will act in relation to the target goal.

3) Ask the individual to build a ‘goal ladder,’ which defines (self-)assessable steps towards progressive goal attainment.

4) Increase the individual’s self-efficacy by showing examples of other patients who achieved a comparable goal, encouraging the patient and praising him or her for goal progress. Teach the individual how to cope with obstacles and relapse.

5) Support goal maintenance, and assist individuals in reformulating their goal in a more manageable way if they find it unattainable in its present form.